1. INTRODUCTION

In

this review titled ‘A Way Forward: Review

of Papua New Guinea’s Millennium Development Goals 2015 Dismal Performance’

I take a look at three recent articles that address the reasons Papua New

Guinea (PNG) had not performed well in its national tailored Millennium

Development Goal (MDG) targets between 2000 and 2015. The reasons range from

technical to geographical and cultural as well as political. In addition, I

would discuss what PNG could do post-2015 to achieve the United Nations’

Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) 2030.

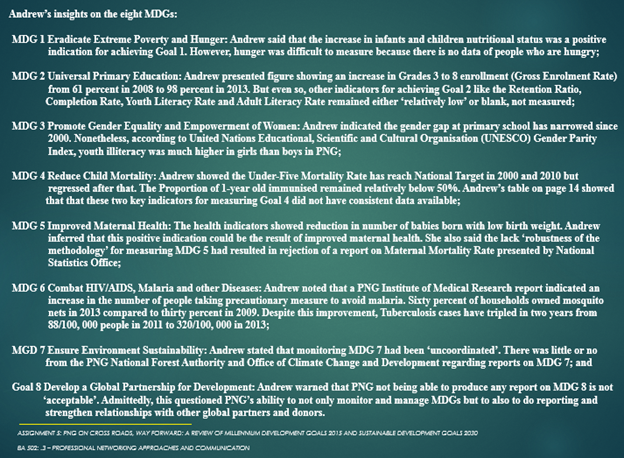

2. ARTICLE 1: THE MILLENNIUM DEVELOPMENT GOALS IN PAPUA NEW GUINEA: THE RESPONSE OF GOVERNMENT

The

article ‘The Millennium Development Goals in Papua New Guinea: the response of government [pdf]’ was written by Marjorie

Andrew, Deputy Director & Research Leader at the National Research

Institute. On the 15th of March, 2015 she presented her research work

at a three-day conference on ‘Resource

Development and Human Well-Being in Papua New Guinea: Issues in the measurement

of progress’. She highlighted several reasons why PNG’s performance on

locally tailored MDGs indicators was ‘off the mark’ (Andrew, 2015, p. 22).

In her remarks on pages 3

- 4, Andrew indicated that PNG national indicators we tailored twice; first in

2004 for the Medium Term Development Strategy 2005 – 2010 and re-tailored in

2010 for Medium Term Development Plan 2011 – 2015. Of the 91 PNG tailored national

indicators, only 40 were the same as the United Nations’ MDGs 1 to 8. The

others (51 tailored indicators) were either blurred or less complying with UN's requirements and therefore cannot be measured internationally. This was of the

reasons why PNG was put in the area of ‘no data’.

On pages 5 - 7, Andrew distinctively pointed

out that the PNG government lacks the internal technical expertise to collect and

analyse important statistical data for the 2015 MDG Progress Report. Though several

departments produced reports annually, overall technical expertise across public

institutions is ‘weak’. She mentioned that PNG’s reliance on international

donors to do reporting showed that without them, vital reports may remain

undone.

3.

ARTICLE

2: MDGS: WHERE DID WE END UP AND WHERE TO FROM HERE?

Dr.

Genevieve Nelson, Chief Executive Officer of Kokoda Track Foundation, gave some

insights on the eight MDGs and put forward several reasons why PNG had

difficulty achieving the MDG indicators. In her introduction, she thought 2015

was ‘...a time to reflect on that past

decade’s [and-a-half] progress towards meeting the goals and setting a new

framework for post-2015’ (Nelson, 2015). Furthermore, she highlighted that

progress was made in the area of poverty reduction worldwide. Quoting McCarter

(2003) she said the estimate for people living under $1.25 per day had halved

from 43 per cent in 1990 down to 21 per cent in 2010 – an indication of a reduction

in poverty. Nonetheless, Dr Nelson said disparity emerged from individual

countries. She clearly indicated that according to the ‘MDG Progress Index

developed by the Centre for Global Development Think Tank’, PNG is awarded a dismal

score of just 1 out of 8.

Dr

Nelson further put emphasis on several challenges why PNG is one of the few

countries in the world that did not meet the MDGs. The two technical reasons she

identified were that the PNG’s tailored development indicators change very

little every few years; and PNG had capacity issues within government offices,

including the government departments. Often there was ‘no data’ in tables due

to their inability to produce reliable data on a regular basis. In addition to

the technical reasons, others reasons that potentially contribute to PNG’s inability

to meet the MDG indicators include Geography, Linguistic and Cultural

diversity, and Governance and Corruption.

Dr.

Nelson remarked that PNG was ranked low on the MDGs Progress Index (1 out of 8)

should be a wake-up call for the government. She reiterated that the ‘business-as-usual’

attitude has to change – there is no room for complacency going forward. PNG

must improve on the technical, geographical, cultural and political challenges,

by developing an appropriate policy framework focused on human development and the provision of services.

In

summary, Dr Nelson said the post-2015 era should see governments, donors,

businesses and NGOs working together to improve people’s lives. Though it may

seem hard, the future of the nation depends on ‘innovation and new technology, collaborations and partnerships, and

strong action focused on the delivery of basic services to remote communities,

to improve outcomes for all Papua New Guineans’ (Nelson, 2015, para. 15).

4. ARTICLE 3: HOW SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT GOALS (SDGs) CAN BENEFIT PAPUA NEW GUINEA’S SOCIETY AND ECONOMY

The

article was written by Ann-Cathrin Joest for an NGO group called the Seed

Theatre Incorporation. Her emphasis was on how PNG could use its lessons

learned on MDGs as a stepping stone for developing a policy framework for the 17

SDGs, post-2015. Joest introduced her article by stating the obvious - PNG had difficulty

achieving the MDGs. She also mentioned that according to the UN’s Human

Development Index (HDI), PNG is rated among the thirty ‘Low Human Development’

(UNDP, 2014) group of countries, ranked 165 out of 187 countries. She also

mentioned that low life expectancies at birth, school retention, maternal

health, high infant mortality and increase sexually transmitted infections were

among the human development issues. Joest also mentioned that PNG is ranked ‘one of the lowest on the Gender Inequality

Index’ (Joest, 2005. para. 2). In addition, she mentioned that urban crimes

and tribal fights were major challenges.

Joest

reasoned that this poor performance was the result of poor education and food

insecurity; inadequate access to sanitation, clean water and energy; and

failure of past and previous governments on its MDG responsibilities. Joest said

that the MDGs expired in 2015. Yet, under those circumstances, the SDGs2030 policy framework

will not be successful post-2015 if the government does not take action to address

issues relating to education, food security, and institutional capacity among

the others.

Furthermore,

Joest contrasted MDGs to SDGs and thought that ‘previous MDGs did not address the root causes for inequalities and

poverty, [while] SDGs address these through the focus on economic development

and human rights (Joest, 2015, para. 5).

5. SUMMARY OF ARTICLES: BUILDING CAPACITY IN PUBLIC INSTITUTIONS, A WAY FORWARD

The

three articles, written last year, had identified several reasons why PNG MDG's performance

was dismal. Dr. Nelson is attempting to discuss a way forward through ‘collaborations and partnerships, and strong

action focused on the delivery of basic services to remote communities' (Nelson,

2015, para. 15) in the post-2015 era would improve people’s standard of living. By

the same token, Joest said PNG’s poor performance in MDGs was the result of

poor education and the failure of [past and current] governments to monitor its MDGs

progress (Joest, 2015).

Both

writers have identified three key areas of service delivery: collaboration,

partnership and government responsibilities. However, to work collaboratively

and in partnership with development partners, the public institutions (and

offices) in PNG needed to take their responsibilities seriously (Andrew, 2015).

There is a need for capacity building in the country in view of the fact that

public institutions either needed donor help in reporting MDGs achievements

(Andrew, 2015) or institutional capacity was ‘weak’ (Andrew, 2015) and unreliable.

On

July the 20th this year, Helen Clark gave an ‘Opening Statement at the High-Level Political Forum (HLPF) Side-Event on “Building Capacities of Public Institutions for Implementing the SDGs: A Focus on Concrete Challenges and Potential Solutions’ said ‘Institutions

which are effective and accountable will play a central role in achieving the

SDGs…the 169 SDG targets make direct reference to the need for institutional

capacity' (Clark, 2015, para. 3). It is seemingly obvious that through capacity

building, PNG can participate effectively and in collaboration with partners

going forward into the SDGs 2030 era.

6. SELF-ASSESSMENT

6.1.

Reflection

on Andrew’s paper

I thought Andrew’s presentation was spot on.

She critically dissected the eight MDGs through her research. She also stated the

obvious fact that the PNG government needed thorough self-examination of its

dismal performance, on the tailored MDG indicators. She further mentioned the

reality that reporting on MDGs progress had been difficult due to a lack of

positive responses from institutional offices like the National Statistics

Office (NSO) and Office of Environment and Conservation (Andrew, 2015, p. 16).

I gather that her use of words such as ‘difficult’ and ‘weak’ was more

diplomatic. But even so, her research experience and the responses showed her

frustration over the lack of capacity from her PNG sources. Though I agree with

most of the facts she produced, she squarely laid the blame on PNG’s

institutional offices she considered to be her data sources for her paper

presentation (Andrew, 2015, p. 16). By way of contrast, little did she

compliment the Department of Education for data on enrolment and retention

(National Education Plan 2005 – 2014 [NEP2005-2014], pp.65 -67), or the NSO

data on Household Income and Expenditure Survey (Andrew, 2015, p.8) she used in

her analyses on MDGs 2 and 1, respectively.

The

point is that though all the data required to compile reports on MDGs were not

available, there was the existence of some form of data in other PNG institutional

offices. As Nelson pointed out, two factors could affect data usage: either there

were few changes over a period of one to two years (Nelson, 2015, para. 8) or

the methodology used at that time to ascertain the use of those data may be

flawed (Nelson, 2015, para. 8). Andrew (2015) inferred that the ‘lack of robustness

of the methodology’ (p. 8) was the reason why the Maternal Mortality Rate (MMR)

produced by NSO was excluded in the MDG Second National Progress Comprehensive

Report 2010. Here, Andrew (2015) saw methodology as the problem rather than

data. Nelson (2015) clearly identified the remedy to this problem (para. 8)

when she implied that methodologies can be adapted, given the type of data

available, to achieve realistic measurements.

6.2. Reflection on Dr. Nelson’s Article

In

addition to technical reasons such as period of data gathering, methodology for

analysing collected data and capacity issues, Dr. Nelson’s article also delved

into other reasons why PNG had not met the MDGs (Nelson, 2015, para. 8). I

thought she had good insight into PNG’s struggles to achieve the MDGs in the last

15 years when she mentioned other reasons like 'Geography, Linguistic and Cultural Diversity, and Governance and

Corruption’ (Nelson, 2015, para. 8). Even though Nelson was succinct in her

explanations, her summary was either difficult to understand with the use of the

word neo-liberal (Nelson, 2015, para. 11) or generalised when she used phrases

like ‘wake-up call’ and ‘business-as-usual’ (Nelson, 2015, para. 11). By this I

mean she was too technical with little explanation or too loose in her choice

of words. Either way, there was a possibility for her readers to misunderstand or

misinterpret what she intended to say.

6.3. Reflection on Joest’s Article

Joest

was explicit in linking the key indicators of MDGs 2015 to SDGs 2030. Her web

article was less academic but more informative. She gave a lot of relevant

opinions on what PNG can do going forward into the SDGs era. She made relevant

connections between each of the 17 goals. For example, ‘With improving poverty (SDG 1), an improvement in malnutrition,

health, education and the economy can take place. With improved food security

and nutrition (SDG2), children or youth can perform better in school. Children

and youth are our future, by investing in their education (SDG4) community

and economic development can take place, better education will generate

increased income which can be directly invested into community health care or

other community needs’ (Joest, 2015, para. 6). In principle, Joest portrayed

an overview of what PNG could do in terms of aligning national policies

framework and termly development strategies and plans going forward (Joest,

2015, para. 6). In saying that, I felt that her article was, more or less, her

personal take on the relevance of SDGs in PNG rather than a practical analysis of

how SDGs could be implemented.

7. CONCLUSION

Finally,

each article showed that PNG performance on its tailored MDG indicators was

dismal. PNG’s nonperformance would only improve if it learned from its past

failures and took a more proactive approach to build capacity within its

public institutions. The writers viewed capacity building at public institutions

as essential for PNG to move forward.

REFERENCES